Hibbleton Film Series presents: We Shall Remain

For the month of May, the Hibbleton Gallery film series will be showing the five-part documentary series WE SHALL REMAIN, which chronicles 400 years of Native American history. All screenings begin at 8pm and are FREE and open to the public. A discussion will follow the film.

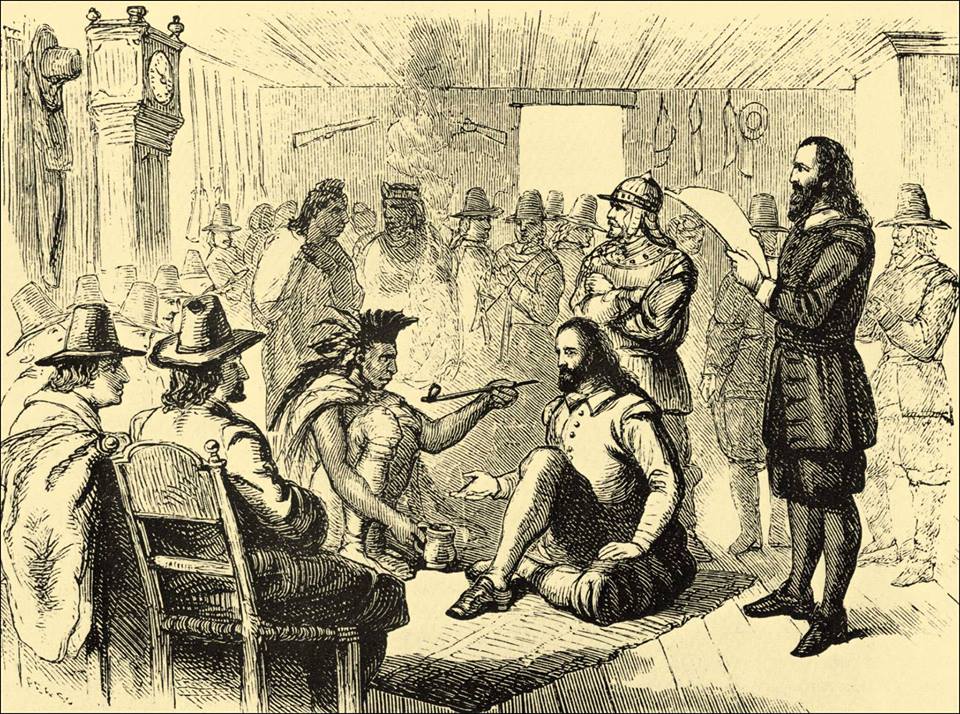

May 1st: AFTER THE MAYFLOWER. In March of 1621, in what is now southeastern Massachusetts, Massasoit, the leading sachem of the Wampanoag, sat down to negotiate with a ragged group of English colonists. Hungry, dirty and sick, the pale-skinned foreigners were struggling to stay alive; they were in desperate need of Native help. Massasoit faced problems of his own. His people had lately been decimated by unexplained sickness, leaving them vulnerable to the rival Narragansett to the west. The Wampanoag sachem calculated that a tactical alliance with the foreigners would provide a way to protect his people and hold his Native enemies at bay. He agreed to give the English the help they needed. A half-century later, as a brutal war flared between the English colonists and a confederation of New England Indians, the wisdom of Massasoit’s diplomatic gamble seemed less clear. Five decades of English immigration, mistreatment, lethal epidemics, and widespread environmental degradation had brought the Indians and their way of life to the brink of disaster. Led by Metacom, Massasoit’s son, the Wampanoag and their Native allies fought back against the English, nearly pushing them into the sea.

May 8th: TECUMSEH’S VISION. In the spring of 1805, Tenskwatawa, a Shawnee, fell into a trance so deep that those around him believed he had died. When he finally stirred, the young prophet claimed to have met the Master of Life. He told those who crowded around to listen that the Indians were in dire straits because they had adopted white culture and rejected traditional spiritual ways. For several years Tenskwatawa’s spiritual revival movement drew thousands of adherents from tribes across the Midwest. His elder brother, Tecumseh, would harness the energies of that renewal to create an unprecedented military and political confederacy of often antagonistic tribes, all committed to stopping white westward expansion. The brothers came closer than anyone since to creating an Indian nation that would exist alongside and separate from the United States. The dream of an independent Indian state may have died at the Battle of the Thames, when Tecumseh was killed fighting alongside his British allies, but the great Shawnee warrior would live on as a potent symbol of Native pride and pan-Indian identity.

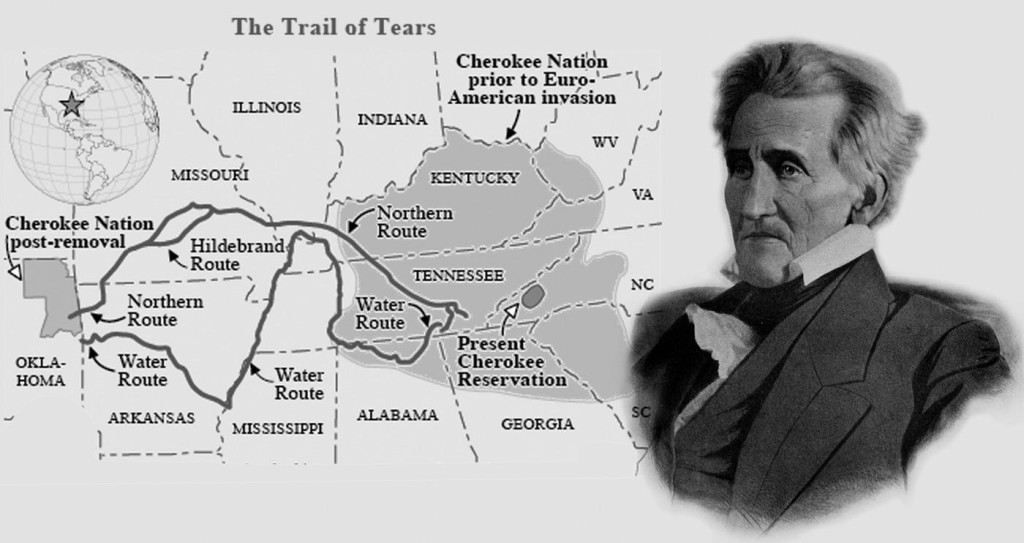

May 15th: TRAIL OF TEARS. The Cherokee would call it Nu-No-Du-Na-Tlo-Hi-Lu, “The Trail Where They Cried.” On May 26, 1838, federal troops forced thousands of Cherokee from their homes in the Southeastern United States, driving them toward Indian Territory in Eastern Oklahoma. More than 4,000 died of disease and starvation along the way. For years the Cherokee had resisted removal from their land in every way they knew. Convinced that white America rejected Native Americans because they were “savages,” Cherokee leaders established a republic with a European-style legislature and legal system. Many Cherokee became Christian and adopted westernized education for their children. Their visionary principal chief, John Ross, would even take the Cherokee case to the Supreme Court, where he won a crucial recognition of tribal sovereignty that still resonates. Though in the end the Cherokee embrace of “civilization” and their landmark legal victory proved no match for white land hunger and military power, the Cherokee people were able, with characteristic ingenuity, to build a new life in Oklahoma, far from the land that had sustained them for generations.

May 22nd: GERONIMO. In February of 1909, the indomitable Chiricahua Apache warrior and war shaman Geronimo lay on his deathbed. He summoned his nephew to his side, whispering, “I should never have surrendered. I should have fought until I was the last man alive.” It was an admission of regret from a man whose insistent pursuit of military resistance in the face of overwhelming odds confounded not only his Mexican and American enemies, but many of his fellow Apaches as well. Born around 1820, Geronimo grew into a leading warrior and healer. But after his tribe was relocated to an Arizona reservation in 1872, he became a focus of the fury of terrified white settlers and of the growing tensions that divided Apaches struggling to survive under almost unendurable pressures. To angry whites, Geronimo became the archfiend, perpetrator of unspeakable savage cruelties. To his supporters, he remained the embodiment of proud resistance, the upholder of the old Chiricahua ways. To other Apaches, especially those who had come to see the white man’s path as the only viable road, Geronimo was a stubborn troublemaker, unbalanced by his unquenchable thirst for vengeance, whose actions needlessly brought the enemy’s wrath down on his own people. At a time when surrender to the reservation and acceptance of the white man’s civilization seemed to be the Indians’ only realistic options, Geronimo and his tiny band of Chiricahuas fought on. The final holdouts, they became the last Native-American fighting force to capitulate formally to the government of the United States.

May 29th: WOUNDED KNEE. On the night of February 27, 1973, 54 cars rolled, horns blaring, into a small hamlet on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Within hours, some 200 Oglala Lakota and American Indian Movement (AIM) activists had seized the few major buildings in town and police had cordoned off the area. The occupation of Wounded Knee had begun. Demanding redress for grievances — some going back more than 100 years — the protesters captured the world’s attention for 71 gripping days. With heavily armed federal troops tightening a cordon around meagerly supplied, cold, hungry Indians, the event invited media comparisons with the massacre of Indian men, women and children at Wounded Knee almost a century earlier. In telling the story of this iconic moment, the final episode of WE SHALL REMAIN examines the broad political and economic forces that led to the emergence of AIM in the late 1960s, as well as the immediate events — a murder and an apparent miscarriage of justice — that triggered the takeover. Though the federal government failed to make good on many of the promises that ended the siege, the event succeeded in bringing the desperate conditions of Indian reservation life to the nation’s attention. Perhaps even more important, it proved that despite centuries of encroachment, warfare and neglect, Indians remained a vital force in the life of America.